This post is the second part of a series of analysis called “Will the Cuban Revolution be digitalised?”, following StartupBRICS exploration of Cuba last August with our connector Brian O’Hagan. You can read the first part here.

Since the transition of leadership from Fidel to Raul in the middle of the 2000s, Cuba has undergone a profound period of transformation. If the Cuban revolution led by Fidel Castro in 1957 was going to survive, let alone thrive, structural changes had to be made in Cuba’s economy. The island has undergone some social (increased Civil Society activity), political (re-opening of diplomatic relations) and economic (private sector growth) changes. However, the process of reform under way in Cuba is not one of reforming into a capitalist country. In this series, I investigate what are the consequences of this transition for the development of entrepreneurship on the Island. I spent three weeks in Cuba meeting with entrepreneurs, tech community builders, students, artists and lobbyist. Unfortunately, I was not able to meet anyone from the Cuban government to help me understand their new brand of socialism.

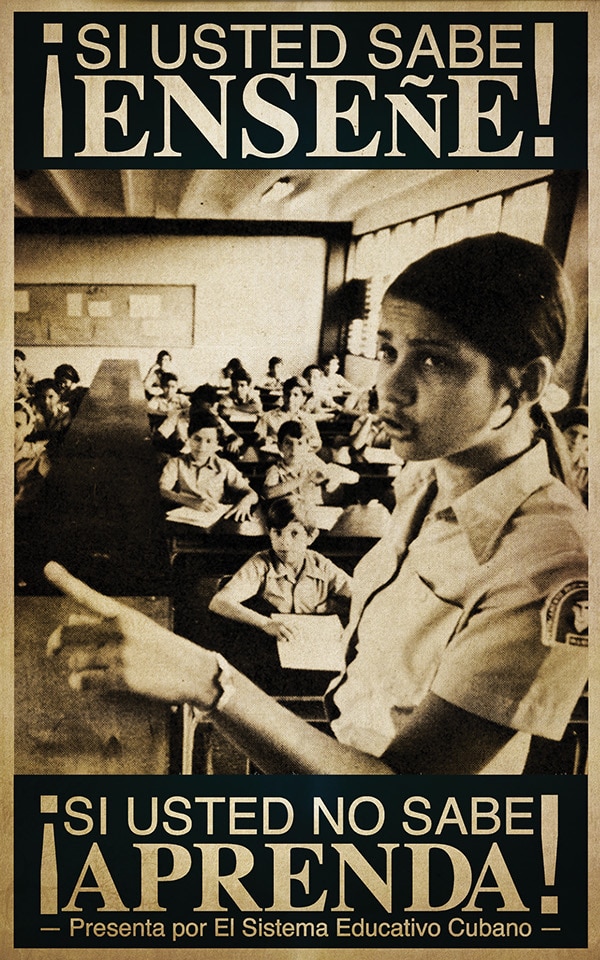

Part 2: The Cuban Education paradox

High in the rainforest of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara were hiding in 1957 among farmers (“campesinos”), plotting the revolution. It is here that the future Cuban leadership discovered that 40% of adults were illiterate, kick-starting a fight that Guevara called the “battle against ignorance”. The first education measure taken by Castro when he arrived to power was the literacy campaign of 1961.

When the literacy campaign was at its height, Fidel Castro began closing all private schools, many of which were run by the Catholic Church. He saw education as having a pivotal role in consolidating his revolution. It prompted the first wave of Cuban exile, noticeably from the teaching elite. The government subsequently invested in universal access to higher education. University education expanded, became free and started focusing on courses that reflected the country’s skill shortages (sciences, engineering, and medicine).

Today, Cubans are extremely well-educated with an astounding 100% literacy rate. Cuba is the 4th country that invests the most in education around the world (13.6% of GDP). The second-largest source of revenue after tourism is the outsourcing of its educated workforce. Two expertise that are typically in shortage around the world have been a source of exports: doctors and engineers.

Cuban doctors regularly go on foreign missions commissioned by the WHO (World Health Organization) in Venezuela, Angola, Brazil and other places needing humanitarian help. This alone generates $ 8B of service export revenue for the government. While Cuban universities are educating many qualified doctors, there is a real medical drug shortage in the country. Medicine is hard to find in pharmacies and cancer drugs are lacking in hospitals due to the country’s financial troubles. This situation is a glimpse into the Cuban paradox: an educated workforce with little means and short of opportunities at home.

Fidel’s “Proyecto Futuro”

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Fidel launched his “Future Project” for two reasons: to computerise the country and develop a software industry to contribute to economic development. Cuba now invests 1.17 % of GDP invested in technological research and development (in comparison, the US invests less than 0.9 percent of GDP). This program has led to the creation in 2002 of the University of Information Sciences (Universidad de las Ciencias Informáticas, or UCI) which has graduated over 14 000 engineers since.

Back in the 1980’s, the computer science faculties were more of an amalgam of researchers from physics and mathematics. Cuba already had world class engineers with members of the international community of internet pioneers. A group of computer science enthusiasts formed the Merchise group at the University “Marta Abreu” of las Villas in Santa Clara. The group explored the possibilities of computer programming with TCP/IP networks, network configuration, graphic design and animation, leading to the creation of a popular role-playing game in Cuba and Mexico: La Fortaleza. It was before the government’s fear of information pushed them to control the internet.

Having being educated in a mostly offline environment, Cuban programmers have a stronger understanding of the theory and mechanics behind programming. Jorge Romero, a member of Merchise group explained “We don’t ask the questions on Stackoverflow – the largest Q&A website for programmers-, we answer them”. It is not uncommon to find many Cubans among the software engineers of the internet giants.

An educated workforce with few opportunities

Unfortunately for the new graduates, the state-owned Cuban ICT industry currently employs only 5,000 workers, mainly in poorly paid government jobs. Most of the founding team of Merchise have emigrated for better-paid jobs abroad. An army of university-educated Cubans are stuck as tourist guides or taxi-drivers because this is where the money is. Doctors and engineers are the two most represented professions in the brain drain affecting Cuba. All this boils down to the fact that engineers and doctors are short of opportunities in Cuba and can pretend to a lot more income abroad.

However, some progress has happened since Raul started leading the country in 2008. He introduced reforms for private sector growth in 2010 allowing 180 professions to become private. Between 2010 and 2015, self-employment licenses known as “cuentapropistas” increased from 105,000 to 505,000. Private-sector employment now accounts for up to 40% of the labor force according to CubaNow. Havana has started to become a software outsourcing hub with small groups of “Cuentapropistas” working as a team. This is the closest thing to a company that the government seems to allow. Cost-wise, Cuban software developers are stunningly competitive with other developing countries: charging US$150-300 per month. Most programmers I have met in Cuba work as freelancers for Latin American or European companies.

More importantly, the government’s rhetoric has been less alienating towards the United States, facilitating Obama’s visit in March 2016. This means more business opportunities with the United States, especially at the tech level. Under a White House policy called “Support for the Cuban People,” amended regulations allow joint ventures with qualified Cuban tech entrepreneurs (both private individuals and cooperatives), as well as the import of their services to the United States. This includes software coding, website design, and the sale of innovative applications under development in Cuba. Cuban engineers are getting prepared to sell to American clients and that’s good news.

This could change under a Trump administration, but it is not yet clear how a Trump presidency will affect US-Cuban relations. Early in his campaign, he said he was “fine” with the Obama policy of rapprochement, but he more recently promised that he will roll-back on Obama’s detente. While Trump has the power to repeal Obama’s executive order, the House and the Senate are now composed of more pro-engagement members than before. The lifting of the embargo can only be done by congress.

Will great education lead to innovation ?

With travel restrictions starting to ease, it will be hard for Cuba to retain its tech talent. Already many Cuban engineers have fled to Ecuador to either work there or start a journey north to the United States. The nation needs to make a better use of the human capital educated over decades at its universities. With such talent, Cuba has the potential to become a hub for technology innovation in its own right. Cuba already has the best technical education and expertise in the Caribbean region, but without access to real internet and capital, it is at risk of losing most of this talent. Cuba’s tech outsourcing community is nonetheless helping to bootstrap a start-up ecosystem.

More on this in the next post.

StartupBRICS Le Blog "Tank" des startups et de l'innovation dans les pays émergents

StartupBRICS Le Blog "Tank" des startups et de l'innovation dans les pays émergents