Opportunities and benefits of technologies in the fight against biodiversity loss

| Let’s talk about Tech 4 Nature. In the scope of the IUCN Congress that was taking place in Marseille, France, from September 3rd to September 11th, this may sounds odd since “Innovation, technology and knowledge” have been a major theme of this edition. However, associating technology and Nature has long been inexistent, or should we say, counterproductive. This statement doesn’t come from us but from Craig Mills, the CEO of Vizzuality, a British data company during his intervention on “Conservation technologies”, a conference given on the stage of the IUCN Congress in Marseille. EMERGING Valley was in the room. By Philippine LECLERC. |

Our perception of technology

Craig Mills decided to start this round table about “conservation technologies” by establishing a picture of what technologies mean and what their uses have been like so far. He started with the meaning given to tech. According to him, when the concept of technology is questioned, it can easily be agreed that tech is a tool. However, it has become far more complex than that. He took as an example social media. If you post a picture of a frog with beautiful eyes and color, you may receive a couple likes. If you add to your caption “picture of a frog taken by a satellite” you will receive a couple of more likes. If you write “Google satellite took this photo”, even more, and this goes on and on. Adding references to technology on social media attracts people’ attention. For Craig Mills there is a simple reason for that: people enjoy technology. More than a tool, it is something people like.

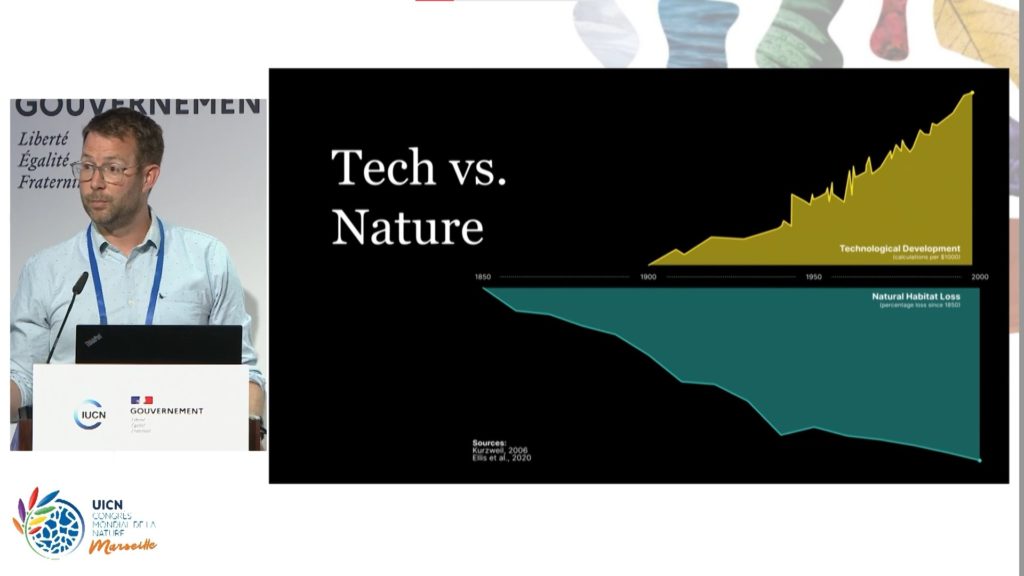

The problems we are trying to solve here in this Congress have largely been the result of human’s use of technology. So when we look at technology today, we have to remember that technology is just a tool that can be used in multiple ways.

Meeting here, at the Global Congress on Nature is quite ambivalent because the problems that stand ahead of us were caused by technology, or humans’ intentions with tech attached to it. Although tech have the ability to be used in multiple ways, it can intentionally or unintentionally be against Nature. Actually, most of the tech uses have never been for Nature. Good thing that today, we want things to change.

Craig Mills took an example to illustrate his thoughts. With his company Vizzuality, he launched a project to monitor global tree cover loss called “Global Forest Watch” 6 years ago. At this time, the ability to analyze massive volume of satellite images to determine where tree loss was happening required an amount of computer power that were not commonly available. Therefore, he had to turn to Google and use their infrastructures to run the analysis. But Mr Mills is raising a point about this. When you think about it, the computers that ran the analysis were paid for by people spending money on advertisement. That’s what Google does, the more clicks, the more money. On the one side, you have technology developed to increase consumption, and on the other side, you use this same technology to fight the effects of its uses. Use and consequence of technology are often hidden. Despite that, the benefits of a project like Global Forest Watch cannot be underestimated. Freely available information, whether codes or data, can be used to monitor at scale and that is what we desperately need today. In a recent report on UK protected areas[1], it was revealed that only 5% of protected areas were effectively protected. Only 5%. So Craig Mills wonders why we didn’t know that sooner. And so is the audience in the room of the conference! Why did we spend resources, time, and money on something that was not working? Why are we witnessing such a failure when technology could and should help us avoid it?

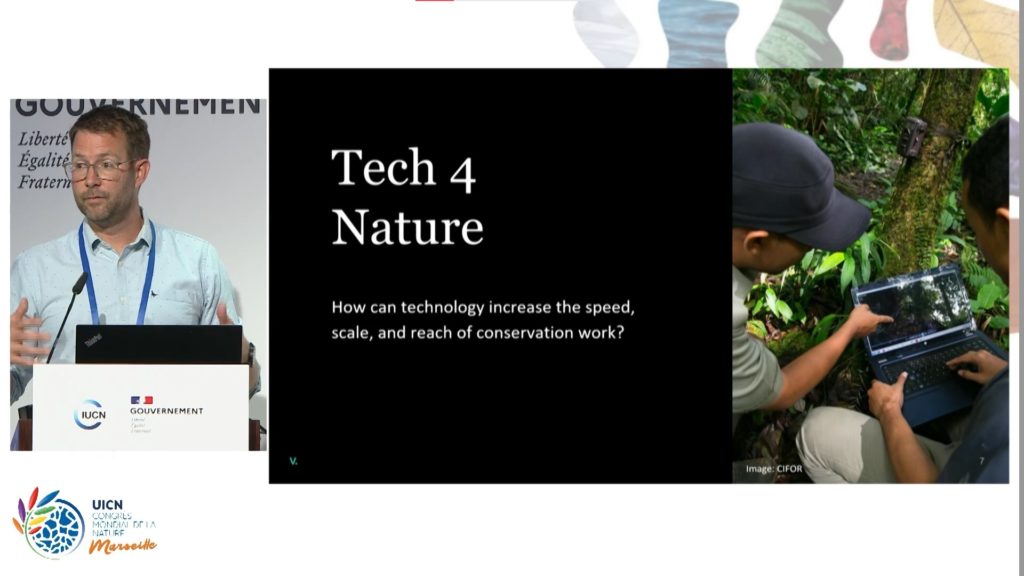

The global agenda on biodiversity is set to 2030. If we want to reach the goals we set, we will need to scale our efforts, knowledge, and technology capacities in a very short period of time. Craig Mills is taking the example of the Marxan Softaware which can be used for systematic conservation planning (the process to determine where the next protected area will be). It is really efficient, but the problem is that it is really hard to use. As of today, only computer science engineers, data analysts, and data engineers can handle it. It has become clear that if we want to reach our 2030 goals, we will need more people capable of using this kind of technology, and we will need to democratize these kind of process.

So the question now is: what do we need to build better tech?

For Mr Mills it can be answered in a few words: human capacity to create technologies suitable for conservation. To reach the goals set, people fluent in data science, computer sciences, and data analysis are urgently needed. Although scale up capabilities will be a difficult task, one thing that can help boost efforts is the growing interest of corporations to bring technology to their internal processes in order to change them for more sustainable ones. As the demand for tech specialists and innovative technologies grows, so is the market, the money flows, and the emergence of new softwares.

If this is an inspiring and positive dynamic, the data and knowledge resources are yet to top the technological tools. In an Economist article,[2]it was estimated that ecosystem modeling is 20 to 30 years behind climate modeling. Quality and quantity of data is a huge problem. To provide data to the engineers working on innovative technologies and software for governments and companies asking for them, data are needed and so are major financial investments. Craig Mills is warning the audience about an underlying risk associated with a growth in investment, which is competition. And that is for the simple reason that playing solo, competing against each other, not sharing information or new processes will not be efficient. If one is producing fundamental data, technology design, or whatsoever, their discovery will have to be open and transparent.

Successful technology is open. It has to be. There is no reason why not.

Our opening speaker emphasized on it again: to reach our 2030 goals and respond to the biodiversity and climate emergency, everybody needs to be successful. Investing in open data is the key to our common and global success. Our classic funding models will no longer be enough and creating new ones will be necessary, whether through unperfect subscription models, or through collaborations between companies sharing the same vision. Convincing people to invest in an ongoing process, that is biodiversity preservation, is difficult. However, it is time for the world to realize that this type of investment will have economic benefits in the long term.

To illustrate Craig Mills’ sayings, a couple of researchers, and companies involved in Technologies 4 Nature were invited to share their doings.

Innovations in field-based measurement.

Natalie Swan, a conservation Project Manager at NatureMetrics, discussed the integration of DNA-based tools in biodiversity monitoring for conservation projects worldwide. NatureMetrics has created an environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling kit that allows anyone to analyze samples coming from the environment. After analysis, this eDNA establishes the presence or absence of species, thus providing a map of their distribution in real time. This tool allows to collect data in a reliable, scalable, and economical way at a time when the lack of available data hinders the implementation of concrete actions in favor of biodiversity preservation.

AI, modelling and big data

Laura Mannocci, a marine ecologist at University of Montpellier, discussed statistical & computational approaches to detect, predict and protect marine megafauna hotspots. She combines the power of deep learning, social networks and aerial photos to achieve this result. More specifically, in order to perfect the species detection models, she trained her artificial intelligences with images of marine mammals available on the web, and videos taken during aerial flights, allowing them to increase their learning and analysis capacities. This method allows to count and locate species, an essential step for the implementation of marine protected areas.

Remote sensing and drone.

Ben Nyberg, a GIS & drone specialist at the National Tropical Botanical Garden Hawaii, discussed connecting technology with on-the-ground surveying and conservation of cliff-dwelling plants. In an ecosystem where 90% of the flora is endemic, and threatened by human’s presence, where there are some 250 single-islands endemic plants with a 1/3 counting less than 50 individuals remaining, and where most of the areas are hard to access, the use of drones became an asset in the Hawaiian biodiversity protection. Their range of action combined with high resolution photography enabled researcher to find and protect several of the rarest species. For example, drones found a plant in 2020 which only had two individuals ever documented. As drones uncovered a group of individuals, botanists were able to secure them in a seed storage and in a nursery. Drones enable to get a better understanding of spatial distribution, habitats requirements, and population numbers, and offer significant conservation outcomes.

[1] Thomas Starnes, Alison E. Beresford, Graeme M. Buchanan, Matthew Lewis, Adrian Hughes, Richard D. Gregory, The extent and effectiveness of protected areas in the UK, Global Ecology and Conservation, 2021,

[2] The Economist. 2021. « Compared with climate, modelling of ecosystems is at an early stage », 15 juin 2021. https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2021/06/15/compared-with-climate-modelling-of-ecosystems-is-at-an-early-stage.

StartupBRICS Le Blog "Tank" des startups et de l'innovation dans les pays émergents

StartupBRICS Le Blog "Tank" des startups et de l'innovation dans les pays émergents